(An excerpt from the novel Etched Upon the Land, unpublished. Copyright 2015 by Pam Wilson. All rights reserved.)

|

The Great Flood

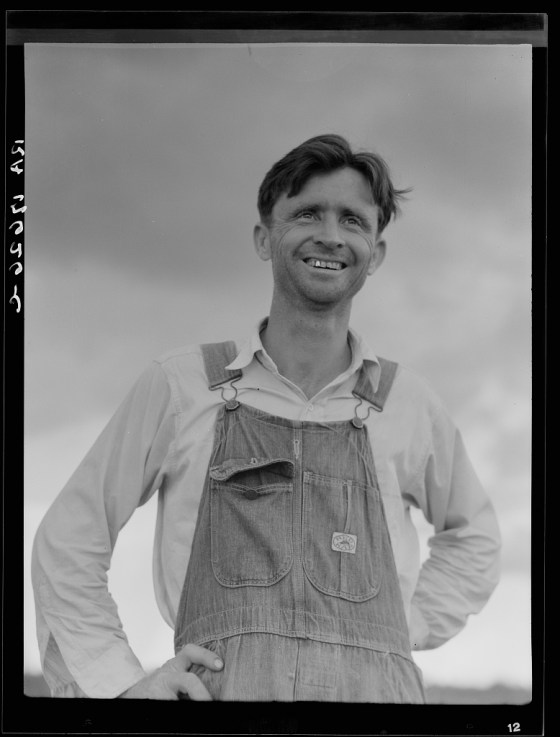

Joe Monahan

1937

I’m carryin’ a great burden, the heaviest burden my soul has ever been forced to bear. ‘Tis a hard life to go on livin’ without my sweet Bernadine and my two angel daughters. I’ve had many a thought of throwin’ myself into the waters of the Ohio these past months, wantin’ to be with them but knowin’ I cannot. And in the end, now, I’ve come to understand that I must bear my burdens like Job and keep on livin’ as best I can.

I’m a simple man, but one raised to have faith. I learned my catechisms. “Faith is the assurance of things hoped for, the conviction of things not seen.” But oh, how hard it is to walk through the darkness of these days, seekin’ understanding and knowin’ that God wants me to persevere. I’m walkin’ by faith, not by sight, through the dark and murky weeks since they’ve been gone, and I often wonder if God has forsaken me altogether. But I know I’m surely not alone. This flood has upturned the lives of hundreds of thousands of folks. I cannot allow myself to succumb to self-pity, even though I’m havin’ trouble seein’ God except “through a glass, darkly,” as it says in First Corinthians.

So now I must keep walkin’. All by myself, for now, until the Lord sees fit to find me some companions. I’m headin’ westward and southward. Leavin’ the places I’ve always known, headin’ into the settin’ sun and away from the damp and the darkness, the smoke and the fires, the ruin and the wreckage. My whole life was washed away down the muddy waters of the Ohio. So I must begin anew. Lonesome but determined.

+++++

My Da crossed the broad waters from Ireland to America as a young man. He worked his way west from Pittsburgh, where he toiled in the mines for a few years, then drifted down the Ohio River to Cincinnati. Danny O’Monahan was a hard-workin’ man who wanted to make a good life for himself. He fell in with other Irishmen who worked on the canals and the railroad and soon married my Mam, who was the younger sister of one of his mates. By that time, he’d changed his name to just Monahan, without the O. His bride’s name was Katie O’Malley, and he said she was the prettiest gal he ever laid eyes upon. They married at Holy Cross Church on Mt. Adams, since her family lived on the East End, but they settled into an apartment on the West End in the bottoms by the river. As the years went on, they had a few young’uns to feed and had saved up a little bit more, so Mam told me they moved up Mill Creek to South Cumminsville, where Mam raised me. Da went off to fight in the Great War and left Mam with four of us at home, but then in 1918 the influenza plague took my baby sister and my brother, next one down from me.

I’ve heard tell that everybody has at least one deciding moment in life when everything changes. I’ve had two, now. The first was in 1918. After the flu took the little ones and Da came home from the war, severe shrapnel wounds in his left arm, life was never the same as before. Mam went to work sewin’ in a dress factory while Da worked in the stockyards until he had too much pain to do the labor. My older sister Doreen married as soon as she was old enough to leave home. I left school and worked in a machine shop to help make ends meet. Da kept up his social activities through the Hibernians and the Friendly Sons of St. Patrick, never lettin’ go of his bein’ Irish. When he was feelin’ well enough, he spent most of his evenings in the pubs with his Hibernian brothers, playin’ the numbers and supportin’ the local breweries, while leavin’ Mam at home to listen to the radio shows and do her needlepoint. I sat with her many nights, enjoyin’ our favorite programs on our hometown station WLW that Mr. Crosley started. We had a Crosley radio, too, the Harko. Mam was so proud of that. That was before Crosley bought the Reds, of course. He turned everyone’s eyes towards the Queen City, all right, by buildin’ the most powerful radio station in the world. But I’m talkin’ about long before that, even before the Crash and the hard times it brought everyone.

Anybody who knows Cincinnati knows it’s a constant contest between the Germans and the Irish. Both bein’ Catholics, however, sometimes we all come together. Well, that’s what happened when I fell in love with Bernadine. She was a good little German girl I met in a shop one day, not long after the Crash. I fancied her from the minute I saw her. Sometimes, you just know someone is the one that’s meant for you. I found somethin’ to ask her a question about to strike up a conversation, then I offered to walk her back home since she was alone and the day was gettin’ late. We had such a good talk as we walked that she agreed to meet me that weekend for another visit. She was a smart girl, finished school and wanted to be a teacher, but couldn’t afford college. By then, I was workin’ part-time in a body shop, pretty good at fixin’ cars. ‘Fore we knew it, we decided to get married. Tied the knot at St. Patrick’s Church in Cumminsville on New Year’s Day in 1932. Bernie moved in with me and my Mam and Da at first until we could settle on a place to live, just the two of us. By then, my sister Doreen had moved out west with her husband Sam, who said he had an itchin’ for the wide, open spaces. We kept gettin’ letters from them as they worked their way west until finally they decided to stop movin’ and settle down in Santa Fe.

Baby Ella came along pretty fast, about a year after we got married. Mam’s place was too small for a growin’ family, so we started lookin’ around for a place to live. Bernie told me she had a hankerin’ to move outside the city, but not so far away like my sister. She said she always wanted a little house by the side of the road with a garden and some fruit trees and a green, grassy yard, not a rowhouse in the city surrounded by factories. Well, I had no idea where or how to start lookin’ for someplace like that, since Cincinnati city life was all I ever knew. Then one day, the fellow I worked for mentioned that his wife’s widowed cousin owned a service station down in Kentucky and was lookin’ for a good man to work on cars for her. When I told him I was interested, he said he’d mention me to her, and I suppose he put in a good word, because she asked for me to call her and then she offered me a job based on his recommendation. Her name was Mrs. Bracht, Lucille Bracht.

Yes, ma’am, my Bernie was so pleased and excited about this. Not only did I have a full-time job, but with a German lady, at that! And Miz Bracht said she knew of a little house down the road we could rent. So I used what little money I’d saved to buy an old car we had in the shop, then Bernie and I packed up our things, loaded up the baby, kissed Mam and Da goodbye and drove down the river toward Warsaw, Kentucky.

Oh, my goodness, it was like a dream come true for Bernie. She got that little house fixed up mighty fine for us. She borrowed Miz Bracht’s sewin’ machine and made curtains, re-upholstered old chairs and a sofa somebody sold to us pretty cheap, and really turned that house into a modest homey place for us and little Ella. Miz Bracht turned out to be a fine woman—quite a businesswoman, to be honest—who also ran a little lunchroom adjoining the service station. It was in Sugar Creek, upriver from Warsaw on the main road, so she got a lot of business and kept a regular crowd comin’ back for more. When the lunchroom clientele became more than she alone could handle, she hired Bernadine to help with the cookin’ and servin’. Bernie’d set little Ella up in a high chair with some toys to keep her occupied while her Mam worked, then had a crib to put her down for her nap when it came time for it.

We had a good life there in Sugar Creek, Bernie and me. Bernie got to be expectin’ again about a year later, but the Lord took that one pretty early along. Before a couple years went by, she found out she was expectin’ again, and this time our luck held out and she had little Irene. We were doin’ pretty good during that time, especially compared to lots of other folks who were without work. We made a decent livin’ workin’ for Mrs. Bracht, and we always had enough food to feed our babies. We didn’t ask for much more than that.

Part of my job was keepin’ Miz Bracht’s station supplied with auto parts and other items, so I drove up to Cincy every few weeks to fill her orders and get stocked up for her. While there, I could check on my parents. My Da passed on after we’d been in Sugar Creek about two years, so I tried to make sure Mam was cared for. She was a right plucky lady for her age, that Katie O’Malley Monahan, still workin’ in the dress factory. She moved into a smaller apartment down in Fairmount, closer to her work and for lower rent. She wrote us letters two or three times a week, and on special occasions we arranged to make long distance calls to her. A few times a year, I’d bring her down to spend a week with us and the girls. She loved gettin’ out of the city and spendin’ time with the little ones. She enjoyed visitin’ with Miz Bracht, too, since they were about the same age. Mam got letters from Doreen every few weeks, too—said they were doin’ real good in Santa Fe and wantin’ us to come visit ‘em. We talked about it and decided we’d save up our money so’s maybe we could all take a train out there one day.

And then, in December 1936, it started rainin’. And life would never be the same.

+++++

Today, it’s four months later, and I’m walkin’, headed west, hopin’ to find a way to reach Santa Fe by summer. Got nearly nothin’ to call my own. The river took it all. So I’m strugglin’ with my faith and puttin’ my feet to the dirt, hopin’ they will carry me where I need to go.

Sometimes the Lord works in mysterious ways. So, I’m just walkin’ along the road, not far from Louisville, my worldly possessions on my shoulder, when a car pulls alongside me. A nice, fancy new Buick, though it’s a little bit dusty from the roads. I admire this car. The Roadmaster’s a beaut. The driver rolls down his window. I see a man about my age, looks like a workin’ man in the face but dressed too fine to be a workin’ man, wantin’ to ask me something. I walk over to him and see there’s a lady in the car with him, too.

“Pardon me, sir, but do you know your way around these parts?” the man asks. I look around me.

“Well, sir, I might be able to help you. Depends on how much detail you’ll be needin’,” I say to him. I see that his plates are from Carolina. He’s a traveler. What could a traveler from Carolina be doin’ in this God-forsaken part of Kentucky a few months after the Great Flood almost wiped it off the map? Must be his map is out of date, or he hasn’t been readin’ the newspapers or listenin’ to the radio.

“Can I give you a lift somewhere?” the man asks. “I’m trying to find my way across the river into Indiana, but I don’t know which bridges might be open or which ones are out.”

I do some thinkin’. I’m kinda good at that. Hmm. If he’s headed west, maybe I could hitch a ride for a while. Take a load off these dogs. Joe Monahan is a proud man, not a beggar, so accepting the kindness of strangers is somethin’ to which I still need to get accustomed.

“That’s mighty kind of you. Tell you what. Let me help get you around Louisville and we’ll find out the situation with the bridges,” I reply. “I’m comin’ from upriver and have heard a lot of news about Louisville, but haven’t seen it first-hand yet.”

The driver of the car stops it, gets out and shakes my hand. He seems like an honorable man. We exchange names briefly, then he opens the back door and makes sure the seat is clear for me. He motions for me to get in. I nod to the woman in the front seat, who asks me how I am, and I tell her I’m doin’ fine and that it’s kind of her to ask. I can tell she’s a bit nervous about havin’ a stranger in her car, though her husband is quite confident. They are young, probably twenties like me. I wonder what their story is.

The husband explains that he and his wife are in the first stretch of a drive across the country. They’ve just left their home in North Carolina less than a week ago, and here they are in western Kentucky, aiming to cross the Mississippi or Ohio. Their goal is to reach California by the end of May, over a month away. They’re goin’ to visit family there.

As we get into the outskirts of Louisville, we see a sign for a diner up ahead. “Would you mind if we stop for lunch here?” the husband asks. “We’d be much obliged if you would join us for our meal. We’ve been driving from Berea early this morning and we’re mighty hungry.”

“Bless you, sir,” I say as we enter the restaurant and I sit down in the diner opposite the nicely-dressed traveling couple. In my own road-worn overhauls, I feel a bit shabby. “Ma’am,” I nod to the wife. “I’m mighty grateful to make your acquaintance. Joe Monahan, by the way.” My eyes follow the husband’s hand as the larger man gestures for the waitress.

“Will you have some coffee, Mr. Monahan?” the husband asks in a kindly tone. I’m hesitant to take charity from strangers, but my reading of this couple is that they seem sincere. And Lord knows, I could surely use a good meal, I think to myself.

“Yes. Thank you, sir,” I say.

“Please call me Ike,” the larger man replies. “No need for formalities among us. Isaac Arledge, but my friends call me Ike. And this is my wife Mrs. Arledge.” I examine his hands. He is indeed a workin’ man—or at least he was. Hands don’t lie. They tell a lot about a person. I look up at his wife.

“Nell,” she says, with a soft smile, extending her hand for a loose handshake. When I take her hand, I feel a vibrant current run between us. She feels it too, because she suddenly looks down, averting her eyes from me, and removes her hand quickly.

“Thank you, Ike, and Mrs. Arledge,” I say with a smile. I’m puzzled by that connection with the wife, not sure what that was or meant.

“Well, Mr. Monahan…,” Ike begins, looking at me earnestly.

“Joe, it is,” I say, reciprocating the friendly offer of lack of formality. I’m still wonderin’ how this man has come upon enough money, in these times, to be drivin’ a 1937 Buick Roadmaster and dressin’ in nice clothes. There’s a story to be told here, if I stick around long enough. Clearly, he’s wonderin’ some things about me, too, as he looks me over.

“Thank you, Joe. What’s your story, sir, if I may ask without intruding too much upon your privacy? What’s put you on the road? You seem like a fine fellow to me, not the wandering kind. Where is your home, and where are you headed?” From the warm and earnest look in his eyes, it’s clear that Ike is sincerely interested. His wife, a lovely petite auburn-haired woman with intelligent eyes, listens intently as well. Should I give them the two-cent version or the two-dollar version? I wonder to myself. I haven’t told my story to too many folks yet. It would be a bit difficult to tell. But I’ll try, I think. Never know what might come of it.

“Well, to tell you the honest truth, it’s surely been a hard few months. The Lord’s been testin’ me mightily. I lost everything I had in the Flood in January. Now I’m aimin’ to start afresh. Heading to New Mexico.”

“Have you got people there, Mr. Monahan?” the wife, Nell, asks, her eyes smiling kindly.

“Yes, ma’am, a sister and brother-in-law. I think they’ll take me in until I get back on my feet.”

“Where are you coming from, Joe?” Ike asks. “What brings a man to leave everything behind?”

He’s blunt and direct, I see, but not in a rude way. He seems to sincerely want to know. “I suppose you’ve heard all about the Great Flood up here in the Ohio River Valley this past winter,” I say, watching for the nods that are forthcoming. “I’ve never seen the wrath of God come with such a fury. It’s a long story. Are you folks sure you want to hear it?” I ask, then watch as they nod, both pairs of eyes intent upon me. “Well, it certainly won’t be easy to tell, but I’ll try.”

The waitress brings our coffee to the table and we give her our order for the lunch plates. As she walks away, Ike says, “We read about the flood in the newspapers and heard reports on the radio. But we’ve not talked first-hand with anyone who survived it. We’d be obliged if you could share your story. Unless it’s just too painful, of course.”

“Yes, sir. I understand. As I said, I’ll try, even though it won’t be easy.” I take a deep breath, then begin. “Well, it’s just mighty hard for me to believe that just three months ago I was livin’ my life, ordinary-like—a happy life with my gal Bernie—Bernadine’s her full Christian name, but I call her Bernie. She’s the prettiest little thing, such a sweet girl and a good wife. And we have our two baby girls, Ella and Irene.” I note Nell’s eyes lighting up in interest. I wonder if she has any little ones yet, I think to myself. I look her over. From her tiny figure, I doubt it, but I might be wrong. My mind goes back to my children.

“Ella’d just turned four. She’s the love of my life, her daddy’s precious little girl. Loves it when I carry her on my shoulders, makes her squeal with glee,” I smile as I remember, tears welling up in my eyes. “She’s a fine little talker, just talked up a storm, a lot like her mama. Bernie’s a real smart woman, wanted to be a teacher if she could’ve gone to college. She’s so good with the girls. Baby Irene wasn’t even walkin’ yet, just startin’ to crawl. She’s still her mama’s girl, still nursin’, didn’t rightly know me much yet.”

I take a deep breath before continuing. Their eyes are still upon me, waiting. They are hardly breathing, either. “We lived right on the Ohio River, on the Kentucky side, just below a big curve in the river called Sugar Creek Bend. Rented a small house on Highway 42 between Sugar Creek and Warsaw, which is a pretty good size little town. Bernie and I’d met in Cincinnati, where we both were reared, but about three years ago I got a job in Sugar Creek with a lady named Miz Bracht, who was lookin’ for an auto mechanic for her service station down here near Warsaw. So we moved down there—that was when Ella was a baby—so I could work in Bracht’s garage and Bernie could help Miz Bracht out in her lunchroom, connected to the service station.”

“How far is Warsaw from Cincinnati?” Ike asks.

“About forty or fifty miles south,” I explain. “Longer if you follow the river all the way. And about twice that far to Louisville.” Ike nods knowingly. He and Nell continue to look at me expectantly.

“So, you probably know the story, but the downpour started at Christmastime. We had heavy rains, about seven inches, between Christmas and New Year’s. Then we got a week’s relief, then another week of misery. This time heavy sleet, since it’d gotten colder, which was followed by another week of rain. We just thought the sky would never empty. It was so cold, too! The temperatures stayed just slightly above freezing—miserable cold, the kind of damp cold that gets in your bones and in your lungs and makes you sick and coughing,” Nell nods as I speak, her eyes still upon me, full of concern.

“But still the cold rains kept a comin’. Rivers and tributaries and creeks all backed up. There wasn’t no place for ‘em to empty out, you know? Those big rivers, the Mississippi and then the Ohio, backed up all the way from Arkansas and through Indiana and Kentucky back to Ohio. Cairo to Paducah to Shawneetown to Evansville, Jeffersonville and Louisville to Warsaw to Cincinnati. Even back to Pittsburgh.”

“The fourth wave o’ storms came on inauguration day when FDR was being sworn in again. Weathermen didn’t know. They just kept guessin’. Every day they told us somethin’ different. We knew it was gonna flood, but they couldn’t tell us how high the crests would be, or when, exactly. The weatherman on WLW Radio kept sayin’ the worst was over. It’d rained nearly 14 inches in January.

“So, I was already almost a week overdue to go for a supply run to Cincinnati for Miz Bracht, needin’ supplies for the station and the restaurant. On Saturday the 23rd, Mr. Devereaux, the metereologist, told us the worst was over, so I decided to drive up to the city to get the supplies and planned to be comin’ home on Monday. I had to check on my mother, too. Miz Bracht assured me she’d take care of Bernie and the girls, for me not to worry. She said they had floods all the time, they’d all go up to higher ground if they needed to. I kissed all my girls goodbye and started up the road toward Cincinnati, got there okay, even got across the bridge from Covington with no problem. That was on Saturday.”

“People in Cincinnati didn’t think it would be too bad. After all, it’s the city of hills, but all the wealthy people live high atop the hills. They really don’t care about what happens in the bottomlands. Folks in Cincinnati are divided by layers. Along the river, real dirt-poor folks live on the waterfront. Next layer up the hill are the Negro folks. Then next up are the Italians and workin’-class Irish and mountain folks from Kentucky and beyond. Further on up the hill you’ll find the Germans, Polish and rich Irish.”

“That was before Black Sunday. January 24, a day I’ll likely never forget all the rest o’ my days here on Earth. New storms came in. Bad storms. River rose to close to 80 feet there in Cincy. I was at my Mam’s, checkin’ on her, and as the waters rose I got her up the hill to higher ground. Red Cross had a shelter up there where they were takin’ people in, and I got her situated. But we had a bird’s eye view of Mill Creek, where I watched the events of that day unfold. When water got into the power plants, it killed electricity. With the temperature droppin’ below freezing, slabs of ice bobbed in the water as Mill Creek backed up and swamped the flood plain. The water was a filthy mix of oil and sewage and dead carcasses. It stunk. We could smell it all the way up the hill, just rushin’ and getting’ higher and higher. Power stations and pumpin’ plants shut down almost all the way, only allowin’ water through the mains for one hour a day, they said. I could see lots o’ people in little boats on the water, too, tryin’ to reach safety. People on their rooftops, climbin’ out the windows of the upstairs, hopin’ to get rescued. I went back down and helped out all the people I could, helped get ‘em to the shelter.

“But the situation on Mill Creek was turnin’ real dangerous. Everybody was scared about fire. Floodwaters smashed debris into oil tanks, gas lines and power lines. All those gasoline storage tanks in Camp Washington got knocked over. One million gallons of gas poured into the Mill Creek. Petroleum tanks were floatin’ downriver, just waitin’ for a chance to explode. Gasoline, kerosene and oil coated the top of the creek, which at this point was at least half a mile wide. We heard there was a leak from Standard Oil refinery. Word went around issuing No Smokin’ orders along the waterfront. But folks couldn’t get cigarettes now if they tried, since all the stores and businesses in town were shut down. The firehouses were buried under the floodwaters, too.”

Ike shakes his head in wonder, while his wife’s face is aghast at the scenes I’m describing. They encourage me to continue.

“Then all holy hell broke loose—please pardon my language, ma’am. Trolley lines were danglin’, live power lines. Didn’t take long ‘fore some of them sparks lit the petroleum on the Mill Creek, down by the Crosley Refrigerator plant and the WLW Radio. We were watchin’ from the hill on the Fairmount side. Gas and oil tanks explodin’ everywhere. Flames built a wall a thousand foot high and burned a path over three miles long. Tire warehouses and God knows what else started burnin’, fillin’ the air with that horrible smell and belchin’ black smoke of burnin’ rubber. The river burned all day and into the night. I never saw anything like the sight of the red flames dancin’ on the black water. They got most of the people evacuated from the neighborhoods in the West End near the fire, but they couldn’t really fight it, just tryin’ to keep people alive as the tops of the houses and buildings stickin’ up above the waterline started burnin’, too.”

“I kept tryin’ to find a telephone to call Bernadine and Miz Bracht to see if they were safe, but all the phone lines were down. I knew Miz Bracht had been livin’ in Sugar Creek for years and had been through some high water, so she’d know what they should do and where to go to reach high ground. I heard the Ohio was thirty foot above flood stage all the way from Cincinnati to Louisville. I didn’t know exactly how high above the river our house was, but bein’ near Sugar Creek tributary meant the creek might flood, too.”

“Took me a couple o’ days to make my way back to where my home had been. Nothin’ was there. Just nothin’. I can’t describe to you how it felt, to see my whole life washed away, not knowin’ what had become of my girls. I started goin’ from camp to camp, shelter to shelter, lookin’ for ‘em. I began to hear the stories. Icy water had flooded way up into the fields. Rescuers had to use pickaxes to chop through the ice to rescue people from their houses. If their houses were still standin’, that is. They told me people close to the river took shelter on higher ground, but a lot o’ towns along the river didn’t have much high ground. People climbed into boxcars of trains, old buildings. They told about bein’ cold, oh, so cold. Livestock drowned or froze. Nobody had nothin’ to eat ‘cept what they carried on ‘em. Some flooders piled possessions on mules or wagons and headed inland and upland, looking for emergency camps or going to their people who lived further from the river.”

“Then the Red Cross started settin’ up camps with tents—tent cities, we started callin’ ‘em—and providin’ shelter and food for people up and down the Valley. Government-issued clothing. Eggs, evaporated milk, canned beef. Prunes and somethin’ called grapefruits, like big round balls with fruit inside. Kinda like an orange, but sour. People’d never seen ‘em, didn’t know how to eat ‘em! They had nurses givin’ typhoid shots, too. I made my way to every shelter and refugee camp up and down the river, from Covington to Louisville, over the next few weeks. Never found Bernadine or the girls. Or Miz Bracht. Nobody had seen ‘em, even the people from Warsaw who knew what they looked like. Along the way, I witnessed the magnitude of people in refugee shelters: Whites, Negroes, Jews, Gentiles, Italians, Irish, Catholics, Protestants and even some Chinese, alike. All livin’ together. Lots of the ones in the shelters’ve been dyin’ of pneumonia, even though they got saved from the water. If the water didn’t get ‘em, the frigid cold got down in their lungs and wouldn’t turn loose.”

“Bless their souls,” Nell says.

“Yes, ma’am, indeed,” I say.

“Surely you found out something about your wife and children?” she asked, hopeful.

I sighed, deeply. “No, ma’am. Unfortunately not. Come to find out 31 houses and buildings between Sugar Creek and Warsaw got swallowed by the Ohio River. Washed clean off their foundations and swept away. They say over half a million are homeless in the Ohio River Valley so far. Not sure how many dead or missin’—up close to a thousand, some say. About a dozen others from that stretch where we lived are missin’, too. Nobody saw or heard from them. They, like my sweet Bernadine and her baby girls, just disappeared into the river, best we can figure. I had another man, who was searchin’ for his own kinfolk, ask at all the shelters on the Indiana side, but no word about them there, either. For a long time, I held out hope that somebody had picked up my family downstream, but then when I heard about the terrible conditions down past Louisville, in Evanston and Shawneetown and Cairo, I began to lose faith and hope.”

“That’s perfectly understandable, Mr. Monahan,” says Nell softly, wiping her tears with Ike’s handkerchief that he had discreetly passed to her a few moments earlier. “Oh, my goodness. God bless you and the memory of your precious family. That’s the saddest and most tragic story I’ve ever heard. You are such a brave man to endure such grievous loss.”

“I beg you not to think of me as brave, ma’am. It was my wife who had the courage to face the ragin’ flood. I did nothin’ to exhibit my bravery. In fact, I’m ashamed to admit to you I was not there to protect my family as I should’ve been.” I hang my head and close my eyes.

“Oh, but surely you cannot blame yourself for their loss, Mr. Monahan!” Nell insists with great compassion.

“There’s nothing to say at a time like this that can be of comfort to you, I know,” Ike says, clearly choked up, “but please know that no one could possibly hold you responsible. It was an act of God.” We remain quiet for a moment, then he continues. “So, Joe, where will you go? What, in heaven’s name, does a man do after a tragedy like this? Brother, you are courageous just to be carrying on,” Ike adds.

I take a deep breath. I find myself exhausted from telling my story, yet it is strangely soothing, too, to share my burden with these kind folks. “I went back to Cincinnati to share the sad news with my mother and my wife’s family. The priest performed a private service in memory of Bernie and the little girls. Of course, they all wanted me to stay there and begin again, perhaps getting’ hired on by the CCC to help rebuild the city. Yet deep in my heart, after much prayer, I came to understand that I have too many memories there. I need to start fresh. So I sent a post to my sister to let her know I’d be on my way to New Mexico, not waitin’ for a response. I sold my car, my only remaining asset, to pay for expenses along the way.”

“How will you get there, Mr. Monahan? What is your plan?” Nell asks me.

“I don’t rightly know, ma’am,” I respond honestly. “I’m a strong man, so I plan to walk westward until I find a better way. If need be, I’ll stop and find work along the way to earn my keep, then continue as I’m able. I imagine I will not be the only wanderer. Once I get further west, I understand, the roads are filled with migrants from the dust bowl.”

“That’s likely true, Mr. Monahan. Joe,” says Ike. “I admire your resolve.” He glances at his wife and they make extended eye contact, as if they are talking without words. She nods, and he turns back to me. “We may not be going the same route you need to go, but we’d like to invite you to ride along with us for as far as you need. We can look at the map and determine the best place for our paths to diverge. Would you honor us with your company for a few days, Mr. Monahan?”

I look at each of them. Their eyes meet mine with sincerity. I can certainly start out with them and see how we all get along. “Well, sir, I’m humbled by your offer. I certainly don’t want to intrude upon your privacy. Let’s try it for a day and then we can decide the best course from there. If you can get me across into Indiana, that would be of great help to me.”

“Louisville will be a shock to both of you, I imagine,” I continue. “After Black Sunday, the Ohio River at Louisville swelled to ten times her normal width, over eight miles wide, and 90% of the city’s homes were flooded up to 30 foot deep. Two thirds of the city population was left without homes. The city of New Albany, Indiana, across the river, was entirely under water. People were bein’ sheltered on any high ground possible, includin’ the airline hangars at Bowman Field. You’ll be passin’ through a disaster zone the likes of which, hopefully, you will never see again.”

Ike reaches across and shakes my hand firmly. “You’re a fine man, Joe Monahan. It’s an honor to us to get the opportunity to know you. Now, if you’ll let me treat you to this lunch, we shall see about getting through the remnants of Louisville and finding our way across the river into Indiana.”

Photo: Dorothea Lange, July 1937, Lot #1676, Works Progress Administration, http://photogrammar.yale.edu/records/index.php?record=fsa2000001454/PP

“The Great Flood” Copyright 2015 by Pam Wilson. All rights reserved.

Photo: Dorothea Lange, July 1937, Lot #1676, Works Progress Administration,

Photo: Dorothea Lange, July 1937, Lot #1676, Works Progress Administration,